In honour of Tamara Spitzer-Hobeika‘s talk on ‘Baudelaire’s dandy: the anti-procrastinator’ (29 October), we look at the unexpected reincarnations of the dandy 6,000 kilometres away from the poet’s hometown. You can find Tamara’s great guest post on Baudelaire and procrastination here.

La SAPE is the world’s most debonair quasi-fictional organization. Featured by everyone from the New York Times to Ireland’s most famous brewery, it purportedly stands for the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes—the Society for Atmosphere-Setters and Elegant Persons.

In reality the organization is probably the invention of migrant youths in Paris and Brussels. In their besuited beings, the dandy is transported from Paris to the twin Congolese capitals, Brazzaville and Kinshasa, and back. If Baudelaire’s dandy is an anti-procrastinator, la sape is a response to externally enforced procrastination. Left in the waiting room of history—through imperial rule and dictatorship at ‘home’, unemployment and discrimination in the European metropolis—the sapeur uses flamboyant high fashion as a refuge and a demand for respect. He (and, like Baudelaire’s dandy, it is always he) embarks on ‘a sort of Baudelairian voyage‘ between continents and ‘from social dereliction to psychological redemption’.

Digital life imitates art: inevitably the Société now has a Facebook page. La sape has a much older history, though, dating back to the first decades of the twentieth century in colonial central Africa. Young Congolese men ‘formed clubs around their interest in fashion, gathering to drink aperitifs and dance to Cuban and European music played on the phonograph’. They invested in canes, silk shirts, fob watches, monocles, gloves—even, we are told, ‘elegant helmets’.

These were not aristocratic dandies in the mode of Beau Brummell, however, but houseboys, bookkeepers, and small traders. They saved up their meagre wages to order the latest Parisian fashions from catalogues or were paid with their bemused masters’ second-hand clothing. The more enterprising even exchanged couture for exotic goods—animal hides, elephant tails.

Sapeur and anticolonial activist Maurice Loubaki and companion in Paris, c. 1931 (from Didier Gondola, ‘La Sape Exposed!’, p. 163)

Through their debonair dress and strict emphasis on personal hygiene, the Congolese sapeurs defied notions of racial inferiority by assuming the trappings of modernity and cosmpolitanism. More than merely imitating French haute couture, they sought to master it—to become connoisseurs. Like the fashionable men of the coast, brought in to man the colonial apparatus, the dignified, dandified native could in this way earn the envious label of mundele ndombe, ‘white with black skins’.

Although borrowing the ‘fashion lexicon’ of colonialism, the sapologist Didier Gondola notes that this process is ‘nonetheless inherently subversive’. In the migrants’ hands, it was swiftly translated into an assimilationist strand of the anticolonial movement. Petitioning for recognition as French citizens, the sapeur-cum-activist demonstrated his credentials with well-chosen accessories: cologne, a close shave, and a white mistress.

The 1950s saw a flowering of night clubs, beer halls, and the Congolese rumba in the twin capitals. Musicians, often paid in boutique clothes, did much to advance the agenda. They incorporated designer labels (or griffes) into their lyrics, and danced as dapperly as they dressed. As the iconic Papa Wemba sang later: ‘Don’t give up the clothes—it’s our religion.’

Mobutu Sese Seko (left) in abacost and demure hat. Resembling a Mao suit or Nehru jacket, the abacost gained popularity with other leaders, including Siyaad Barre.

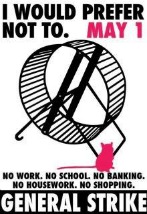

La sape was politicized once more in the face of the social tensions of 1960s Zaire. In 1974 President Mobutu banned Western suits and ties as part of his ideological programme of Authenticité, an attempt to ‘Zairianize’ national identity and eradicate the vestiges of colonialism. The suit was replaced by the abacost, an abbreviation of à bas le costume, ‘Down with the suit!’

In this context, the designer-suited sapeurs took on a radical light, their dress and public gatherings a form of civil disobedience. Some even developed manifestos and codes—though these focused more on the Ten Best Ways of Walking to Flaunt Your Versace, rather than freedom of assembly.

Imelda Marcos, eat your heart out. Sapeurs became known for taking man-powered rickshaws to protect their shoes, much to the irritation of the nominally Marxist-Leninist regime in Republic of Congo, which banned the practice. The J.M. Weston gold crocodile penny loafers on the left are worth $1,750. In 2013, annual per capita GDP (at purchasing power parity) in the Democratic Republic of Congo was $747.

Today’s sapeurs are at least the third generation, and proudly boast of their pedigree. With a cigar and a bottle of beer in hand, they exude a sense of relaxed opulence. Their styles have updated with the times, now including London designers, kilts and tam-o’-shanters in imitation of an unlikely style icon: Prince Charles.

But, for all their Kenzo ties and Yohji Yamamoto jackets, la sape remains the hallmark of an underclass. For the Congolese psychology professor François Ndebani, la sape is a ‘hotbed of delinquency’, fuelled by drugs. In the banlieues of Europe, too, Congolese migrants face discrimination and underemployment. In the face of this, the sapeur is a defiant figure, dodging train fares and dominating public space to claim back the ‘colonial debt’. Self-respect is the priority: as one sapeur says, ‘A Congolese sapeur is happy even if he does not eat.’

Just as the uncompromising sensibility of Baudelaire’s dandy became equated with vacuous foppism and Walter Benjamin’s arcades with the Americanized mall, the sapeurs have been coopted. Congo-Brazzaville president Denis Sasou Nguesso elevated la sape as a form of cultural heritage, sponsored by the Ministry of Tourism. He slips into designer suits for foreign trips, earning him the nickname of ‘the Pierre Cardin Marxist’.

In the West, too, the picturesque sapeurs have been safely recast as the consumerist icons of a rising Africa. Solange Knowles, Beyoncé’s little sister and famed Jay-Z basher, drafted them in for a 2012 music video. In January 2014 Guinness built an advert around la sape, prompting a wave of media interest. (Both videos were actually shot in South Africa.) Quoting—what else?—the poem ‘Invictus’, the growly voiceover declares: ‘In life, you cannot always choose what you do, but you can always choose who you are.’

Youth unemployment is becoming a hallmark of the twenty-first century. With little money and even fewer prospects, accused of procrastination and fecklessness, young men must pass the time. By taking up the dandy’s mantle and making themselves living works of art, are the sapeurs flamboyant rebels—or mere fodder for the fashion industry?

One story—our favourite—places the origin of the cult at a convent in Paris. In 1781, a package containing unidentified relics and statutes that had been unearthed at the Denfert-Rochereau catacombs in the city was delivered to the nuns of a nearby convent. Not knowing anything about the martyr to whom the relics belonged, the nuns did what all of us would do: they checked the box for instructions. Lo, the box was marked expedite: the remains must be St. Expeditus! (Forget that expédite is “sender”, please—I’m telling a story.) When their prayers to the new martyr were answered with lightening speed, the cult of Expeditus spread with equal haste across France, and then to all of Christendom. While you wait for the urban legend bells to subside, spare a thought for some nuns duped by express delivery.

One story—our favourite—places the origin of the cult at a convent in Paris. In 1781, a package containing unidentified relics and statutes that had been unearthed at the Denfert-Rochereau catacombs in the city was delivered to the nuns of a nearby convent. Not knowing anything about the martyr to whom the relics belonged, the nuns did what all of us would do: they checked the box for instructions. Lo, the box was marked expedite: the remains must be St. Expeditus! (Forget that expédite is “sender”, please—I’m telling a story.) When their prayers to the new martyr were answered with lightening speed, the cult of Expeditus spread with equal haste across France, and then to all of Christendom. While you wait for the urban legend bells to subside, spare a thought for some nuns duped by express delivery.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.