Anna Della Subin, our conference programme declared, ‘writes about sleepwalkers, grave worship, animal rights in Cairo, mummies, imperial Ethiopian court etiquette, visions of the flood, thirteenth-century occulists, 300-year naps, resurrection, men becoming gods, and gods becoming men.’

Now our multitalented speaker has provided a wonderful précis of our 2 July conference, and a novel take on embracing idleness, in this weekend’s New York Times. See below—or click here for the original, complete with zingy cartoons by Viktor Hachmang.

How to Stop Time

“Procrastination, quite frankly, is an epidemic,” declares Jeffery Combs, the author of “The Procrastination Cure,” just one in a vast industry of self-help books selling ways to crush the beast. The American Psychological Association estimates that 20 percent of American men and women are “chronic procrastinators.” Figures place the amount of money lost in the United States to procrastinating employees at trillions of dollars a year.

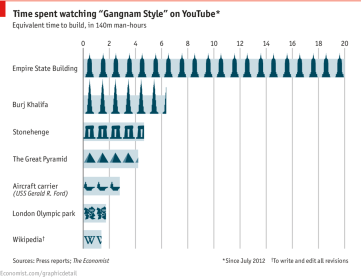

A recent infographic in The Economist revealed that in the 140 million hours humanity spent watching “Gangnam Style” on YouTube two billion times, we could have built at least four more (desperately needed) pyramids at Giza. Endless articles pose the question of why we procrastinate, what’s going wrong in the brain, how to overcome it, and the fascinating irrationality of it all.

But if procrastination is so clearly a society-wide, public condition, why is it always framed as an individual, personal deficiency? Why do we assume our own temperaments and habits are at fault—and feel bad about them—rather than question our culture’s canonization of productivity?

I was faced with these questions at an unlikely event this past July—an academic conference on procrastination at the University of Oxford. It brought together a bright and incongruous crowd: an economist, a poetry professor, a “biographer of clutter,” a queer theorist, a connoisseur of Iraqi coffee-shop culture. There was the doctoral student who spoke on the British painter Keith Vaughan, known to procrastinate through increasingly complicated experiments in auto-erotica. There was the children’s author who tied herself to her desk with her shoelaces.

The keynote speaker, Tracey Potts, brought a tin of sugar cookies she had baked in the shape of the notorious loiterer Walter Benjamin. The German philosopher famously procrastinated on his “Arcades Project,” a colossal meditation on the cityscape of Paris where the figure of the flâneur—the procrastinator par excellence—would wander. Benjamin himself fatally dallied in escaping the city ahead of the Nazis. He took his own life, leaving the manuscript forever unfinished, more evidence, it would seem, that no avoidable delay goes unpunished.

As we entered the ninth, grueling hour of the conference, a professor laid out a taxonomy of dithering so enormous that I couldn’t help but wonder: Whatever you’re doing, aren’t you by nature procrastinating from doing something else? Seen in this light, procrastination begins to look a lot like just plain existing. But then along come its foot soldiers—guilt, self-loathing, blame.

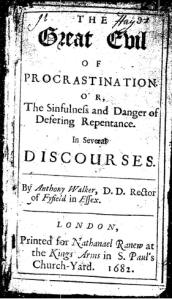

Dr. Potts explained how procrastination entered the field as pathological behavior in the mid-20th century. Drawing on the work of the British-born historian Christopher Lane, Dr. Potts directed our attention to a United States War Department bulletin issued in 1945 that chastised soldiers who were avoiding their military duties “by passive measures, such as pouting, stubbornness, procrastination, inefficiency and passive obstructionism.” In 1952, when the American Psychiatric Association assembled the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—the bible of mental health used to determine illness to this day—it copied the passage from the cranky military memo verbatim.

And so, procrastination became enshrined as a symptom of mental illness. By the mid-60s, passive-aggressive personality disorder had become a fairly common diagnosis and “procrastination” remained listed as a symptom in several subsequent editions. “Dawdling” was added to the list, after years of delay.

While passive-aggressive personality disorder has been erased from the official portion of the manual, the stigma of slothfulness remains. Many of us, it seems, are still trying to enforce a military-style precision on our intellectual, creative, civilian lives—and often failing. Even at the conference, participants proposed strategies for beating procrastination that were chillingly martial. The economist suggested that we all “take hostages”—place something valuable at stake as a way of negotiating with our own belligerent minds. The children’s author writes large checks out to political parties she loathes, and entrusts them to a relative to mail if she misses a deadline.

All of which leads me to wonder: Are we imposing standards on ourselves that make us mad?

Though Expeditus’s pesky crow may be ageless, procrastination as epidemic—and the constant guilt that goes with it—is peculiar to the modern era. The 21st-century capitalist world, in its never-ending drive for expansion, consecrates an always-on productivity for the sake of the greater fiscal health.

In an 1853 short story Herman Melville gave us Bartleby, the obstinate scrivener and apex procrastinator, who confounds the requests of his boss with his hallowed mantra, “I would prefer not to.” A perfect employee on the surface — he never leaves the office and sleeps at his desk—Bartleby represents a total rebellion against the expectations placed on him by society. Politely refusing to accept money or to remove himself from his office even after he is fired, the copyist went on to have an unexpected afterlife—as hero for the Occupy movement in 2012. “Bartleby was the first laid-off worker to occupy Wall Street,” Jonathan D. Greenberg noted in The Atlantic. Confronted with Bartleby’s serenity and his utter noncompliance with the status quo, his perplexed boss is left wondering whether he himself is the one who is mad.

A month before the procrastination conference, I set myself the task of reading “Oblomov,” the 19th-century Russian novel by Ivan Goncharov about the ultimate slouch, who, over the course of 500 pages, barely moves from his bed, and then only to shift to the sofa. At least that’s what I heard: I failed to make it through more than two pages at a sitting without putting the novel down and allowing myself to drift off. I would carry the heavy book everywhere with me—it was like an anchor into a deep, blissful sea of sleep.

Oblomov could conduct the few tasks he cared to from under his quilt — writing letters, accepting visitors — but what if he’d had an iPhone and a laptop? Being in bed is now no excuse for dawdling, and no escape from the guilt that accompanies it. The voice—societal or psychological—urging us away from sloth to the pure, virtuous heights of productivity has become a sort of birdlike shriek as more individuals work from home and set their own schedules, and as the devices we use for work become alluring sirens to our own distraction. We are now able to accomplish tasks at nearly every moment, even if we prefer not to.

Still, humans will never stop procrastinating, and it might do us good to remember that the guilt and shame of the do-it-tomorrow cycle are not necessarily inescapable. The French philosopher Michel Foucault wrote about mental illness that it acquires its reality as an illness “only within a culture that recognizes it as such.” Why not view procrastination not as a defect, an illness or a sin, but as an act of resistance against the strictures of time and productivity imposed by higher powers? To start, we might replace Expeditus with a new saint.

Albert Cossery. Image from New Directions

At the conference, I was invited to speak about the Egyptian-born novelist Albert Cossery, a true icon of the right to remain lazy. In the mid-1940s, Cossery wrote a novel in French, “Laziness in the Fertile Valley,” about a family in the Nile Delta that sleeps all day. Their somnolence is a form of protest against a world forever ruled by tyrants winding the clock. Born in 1913 in Cairo, Cossery grew up in a place that still retained cultural memories of the introduction of Western notions of time, a once foreign concept. It had arrived along with British military forces in the late 19th century. To turn Egypt into a lucrative colony, it needed to run on a synchronized, efficient schedule. The British replaced the Islamic lunar calendar with the Gregorian, preached the values of punctuality, and spread the gospel that time equaled money.

Firm in his belief that time is not as natural or apolitical as we might think, Cossery, in his writings and in his life, strove to reject the very system in which procrastination could have any meaning at all. Until his death in 2008, the elegant novelist, living in Paris, maintained a strict schedule of idleness. He slept late, rising in the afternoons for a walk to the Café de Flore, and wrote fiction only when he felt like it. “So much beauty in the world, so few eyes to see it,” Cossery would say. He was the archetypal flâneur, in the footsteps of Walter Benjamin and Charles Baudelaire, whose verses Cossery would steal for his own poetry when he was a teenager. Rather than charge through the day, storming the gates of tomorrow, his stylized repose was a perch from which to observe, reflect and question whether the world really needs all those things we feel we ought to get done—like a few more pyramids at Giza. And it was idleness that led Cossery to true creativity, dare I say it, in his masterfully unprolific work.

After my talk, someone came up to ask me what I thought was the ideal length of a nap. Saint Cossery was smiling. Already one small battle had been won.

To Oxford, that humming hive of academic endeavour and fantastical far-niente, for a cultural exploration of procrastination convened by the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing.

To Oxford, that humming hive of academic endeavour and fantastical far-niente, for a cultural exploration of procrastination convened by the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing. Hurry up please, it’s time.

Hurry up please, it’s time.