We are living in the Age of the List. Its empire extends from the crags of the Encyclopædia Britannica to the sweaty coast of BuzzFeed. There is a list for every second of the day, from Disney’s original 47 dwarves to the spiritually troubling effects of the baby aardvark. ‘Lists,’ as Don DeLillo declaimed twenty years ago, ‘are a form of cultural hysteria.’ They have colonized our food, our news, our emotions. They even got Wallace Stevens.*

As every procrastinator knows, Stage 1 in the self-help world is the To-Do List. Even the first usage of ‘list’ in this sense—’a catalogue or roll consisting of a row or series of names, figures, words, or the like’—the OED attributes to none other than Hamlet’s more decisive echo (Horatio: ‘Young Fortinbrasse..Hath..Sharkt vp a list of lawelesse resolutes’). The list is the communion wafer of the productivity cult that is Getting Things Done and has spawned a thousand apps.

As every procrastinator knows, Stage 1 in the self-help world is the To-Do List. Even the first usage of ‘list’ in this sense—’a catalogue or roll consisting of a row or series of names, figures, words, or the like’—the OED attributes to none other than Hamlet’s more decisive echo (Horatio: ‘Young Fortinbrasse..Hath..Sharkt vp a list of lawelesse resolutes’). The list is the communion wafer of the productivity cult that is Getting Things Done and has spawned a thousand apps.

- Break it down.

- Make a list.

- Just do it.

Simple.

But what if the list is not the silver bullet we were promised? Many über-procrastinators are diligent list-makers. My room is piled higher and deeper with shopping lists and future bibliographies, playlists and New Year’s Resolutions, holiday wish lists and 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.

Why do my lists (crafty inky things) betray me? Here are 11 ways 7 ways that lists can go dreadfully wrong—and why we carry on writing them anyway.

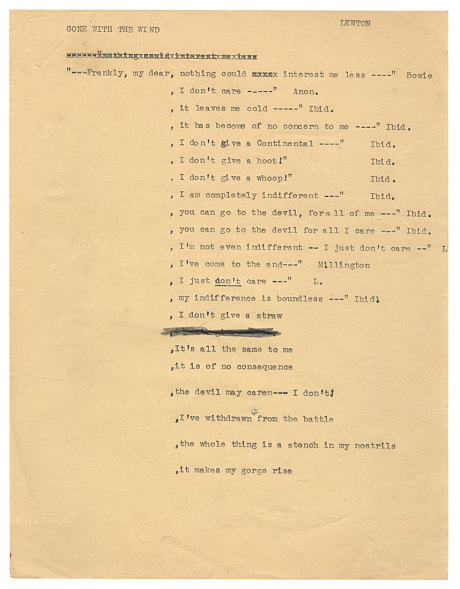

Last-minute alternatives to Gone With the Wind‘s most famous line, after US censors decided ‘damn’ was too wild. From Lists of Note (ed. Shaun Usher, 2014).

1. Lists create a false sense of achievement. They are beautifully time-consuming in their own right. One journalist writes that list-making is ‘is the most effective temporary form of anxiety relief that I know of’—’aside from heavy drinking’, of course. Describing the ‘bliss, euphoria and an all-consuming calm’ that writing a list brings, another confesses, ‘It doesn’t matter that I will never look at it again.’ (The profession may attract some troubled individuals.)

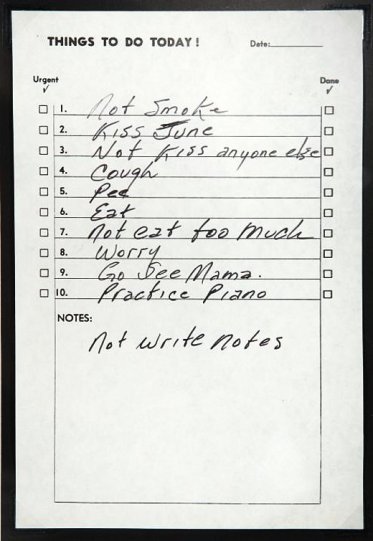

Worse, you can cheat in your pursuit of the list buzz. Who hasn’t added something they’ve already done? The first item on any true procrastinator’s list is: ‘1. Make List.’ Or look at this famous example by Johnny Cash:

‘Cough. Pee. Eat.’ Might we be setting the bar a tad low?

2. This weird pleasure is down to the self-reinforcing joy of completeness. This is the ‘reassuring allure’ of the listicle: we can commit to their tiny size, and yet feel smug about conquering them. This low-effort completism is the curse of the perfectionist procrastinator, for the illusion of self-improvement that it fosters. You really ought to be able to name all 54 countries in Africa. Might as well binge-watch all of Orange Is the New Black now, so it doesn’t distract you tomorrow. And what if someone starts chatting about the Sixth Ecumenical Council at dinner? Click. Click. Click.

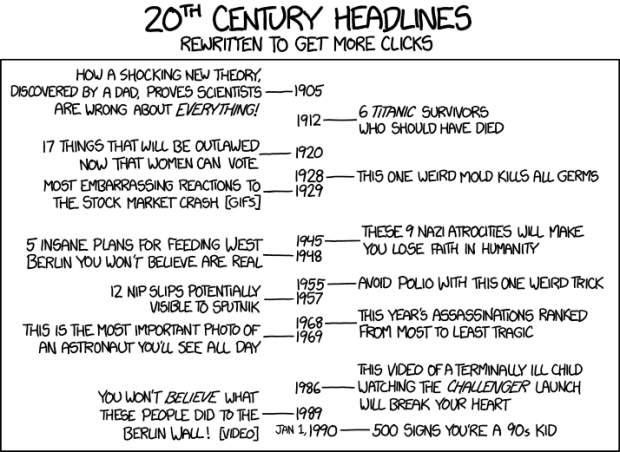

‘Lists mean likes!’ —XKCD

3. On the other side of the spectrum, lists are often aspirational rather than attainable. They are to work as the Ikea instruction manual is to the Fjälkinge. Their relationship to reality is tenuous. The archetype is the bucket list, condemned by the New Yorker as ‘the YOLO-ization of cultural experience.’ A quick perusal of those astute folks on the internetz brings up the following mortality-cheating goals:

- Learn how to knit

- Paint smiles on all the eggs in fridge

- Get stuff coated in gold

- Discover element. Name after self.

- Touch Christian Bale’s face

Just like my to-do lists: 40% banality, 60% wishful thinking.

4. Lists are the lazy man’s way of imposing order. They make a superficial kind of sense. Never mind that this order can be entirely arbitrary:

In its remote pages it is written that the animals are divided into: (a) belonging to the emperor, (b) embalmed, (c) tame, (d) sucking pigs, (e) sirens, (f) fabulous, (g) stray dogs, (h) included in the present classification, (i) frenzied, (j) innumerable, (k) drawn with a very fine camelhair brush, (l) et cetera, (m) having just broken the water pitcher, (n) that from a long way off look like flies.

— Jorge Luis Borges, a ‘certain Chinese encyclopaedia entitled “Celestial Empire of benevolent Knowledge”‘

This explains why so many academics love lists. They fit on PowerPoint slides, ensuring most social science presentations are a firing squad of bullet points.

THE LAKE. THE NIGHT. THE CRICKETS. THE RAVINE. THE ATTIC. THE BASEMENT. THE TRAPDOOR. THE BABY. THE CROWD. THE NIGHT TRAIN. THE FOG HORN. THE SCYTHE. THE CARNIVAL. THE CAROUSEL. THE DWARF. THE MIRROR MAZE. THE SKELETON.

That was Ray Bradbury building a story. But it could just as well have been that anthropology seminar you sat through last Tuesday.

5. It’s easy to assume that if you imitate the trappings of horrifying overachievement, you’ll become a horrifying overachiever yourself. And successful people love lists.

But what if overachievers don’t make the best advisors? Zadie Smith summarized:

When still a child, make sure you read a lot of books. Spend more time doing this than anything else.

Thanks, Zadie. Other authors you might consider imitating (from Mason Currey’s great Daily Rituals):

- Francis Bacon: dined on rich food, a half-dozen bottles of wine, and garlic pills

- Ayn Rand: worked for 30 hours straight, powered by Benzedrine

- Patricia Highsmith: kept pet snails, which she smuggled into cocktail parties in her handbag

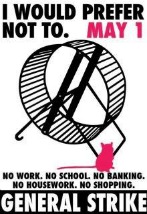

6. Once that deadline’s whizzed by, lists help you work out who to blame. Blacklists, grudge books, hit lists—all jolly distractions from the tedium of actual work.

7. Lists can grow and shrink along with your sense of self. You can relabel your blog post ‘7 Reasons’ because you kind of ran out before 11. Or they can take on a momentum all of their own: an academic we know is writing a book on reference works, from Samuel Johnson to Hobson Jobson, and has an entire chapter entitled ‘overlong and overdue’. Lists are potentially infinite. For Umberto Eco, this explained why we love them: ‘because we don’t want to die’.

Isn’t this exactly what procrastination is—the triumph of hope over experience?

_

* Do not click on these links. THEY ARE TRAPS.

29 October: John McManus,

29 October: John McManus,  Tamara Spitzer-Hobeika,

Tamara Spitzer-Hobeika,