Oxford is, without doubt, one of the cities in the world where least work gets done.

—Javier Marías, All Souls (Todas las Almas, 1989)

Is Oxford especially procrastination-prone? Despite its profusion of clocks (‘The bells! The bells!’), the city prides itself on its timelessness. The spires dream. It is a ‘city preserved in syrup’, like an old-fashioned peach, or a dead wasp. Perhaps it is no accident that Alice in Wonderland was written here: a book of eternal teatime, where time is murdered, and it is always six o’clock.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.

Surveying this literature, here are three key reasons why Oxford is the venerable home of procrastination.

Walls

Academic seclusion has all the inconveniences of a desert island, with none of its compensations: it breeds idleness, spite, intrigue, arrogance and strange lunacies.

—Cecil Day Lewis and Charles Fenby, Anatomy of Oxford (1938)

Oxford’s walls and cloisters are a blessing and a curse. On the plus side, eccentricity, brotherhood, and tradition flourish. On the negative side, eccentricity, brotherhood, and tradition flourish. Jan Morris compared it to Kyoto: old, intensely private, provincial and stubborn.

Into the 1800s, unreformed Oxford was notably relaxed about academic work. The historian Edward Gibbon claimed that the fourteen months he spent at Magdalen were ‘the most idle and unprofitable of my whole life’. Adam Smith accused the professors of giving up ‘even the pretence of teaching’. John Wesley delivered a ferocious sermon at the University Church in 1744, castigating the university fellows for their

pride and haughtiness of spirit, impatience and peevishness, sloth and indolence, gluttony and sensuality, and even a proverbial uselessness.

(He was banned thereafter.)

Even in the twentieth century, Oxford’s ‘narrow serenity’ persisted, albeit with an increasing sense of paradise lost. The students joined drinking clubs and whipped off their trousers (Evelyn Waugh, Decline and Fall), or pinioned Jewish students ‘to the lawns with croquet-hoops’ (Jake’s Thing). Meanwhile the university fellows declaimed, discoursed, plotted and schemed, mounted the hierarchy, and exercised their eccentricities. Committees, lectures, papers, marking, and those pesky students: Isaiah Berlin (see our Cunctator Prize) complained of the ‘fearful time-eating occupations’ of university life, ‘devouring one’s substance’. The whole logic is that of Sayre’s Law—academic politics are so vicious precisely because the stakes are so small. Recall that one of the fiendish tactics of Gaudy Night‘s villain was… maliciously blocking the SCR lavatories.

With all these other claims on their time, how could anyone get any work done?

High Street

In my first-ever tutorial, the professor asked us whether we had ‘developed any new vices’.

Max Beerbohm by Walter Sickert in Vanity Fair (1897)

‘No?’ He whipped out a box of snuff.

No wonder Oxford is so serene. It’s drug-addled. And it’s a city of temptations. This is the tranquillized city that inspired a hookah-smoking caterpillar. Northern Lights begins in the Retiring Room of Jordan College, complete with ‘a basket of poppy-heads’.

Or else the Fellows are all drunk, as a German visitor complained in 1710. Little had changed 250 years later. So Philip Larkin could scribble: ‘I drove v. carefully after my 2 gins, 3 wines, 2 ports and 1 whiskey, a v. modest All Souls evening.’ Undergraduates learned from the best. ‘I cut tutorials with wild excuse, / For life was luncheons, luncheons all the way,’ Betjeman wrote (he was sent down).

Mind you, those opium dreams can be inspiring if not terribly productive, as Coleridge might tell you. ‘Oxford, that lotus-land, saps the will-power, the power of action’, Max Beerbohm began,

But, in doing so, it clarifies the mind, makes larger the vision, gives, above all, that playful and caressing suavity of manner which comes of a conviction that nothing matters, except ideas. —Zuleika Dobson (1911)

Pride and prejudice and zombies

Perhaps there is an even simpler explanation for the epidemic of lethargy. Oxford is a city of the undead.

Image via bloodymurder.wordpress.com

Those ghostly moonlit towers are a clear breeding ground for phantoms. Think of all those detectives: Morse and Lewis, Lord Peter Wimsey, Gervase Fen, Dirk Gently. Poison, bludgeonings, gargoyle landslides, the odd mass suicide engendered by a foxy lady… There can be barely 27 of us still alive in here.

Some of its most famous alumni had the measure of the city. Algernon Swinburne claimed nobody in Oxford could be said to die ‘for they never begin to live’. Mere months after arriving at Merton College, T.S. Eliot agreed that ‘Oxford is very pretty, but I don’t like to be dead’, and fled to London. ‘It is as though the genius of the city dries up the sap in you,’ wrote Jan Morris. The blood of its scholars, like Middlemarch‘s Casaubon, contains not human red blood cells but semicolons and parentheses.

Others have explicitly alerted us that the dead are walking Turl Street. Much-lampooned broadcaster Robert Robinson set his 1956 crime hit Landscape with Dead Dons in Warlock College. More recently the hero of Deborah Harkness’s historical fantasy trilogy (2011-) is, inevitably, a vampire at All Souls (or ‘the love child of a wedding cake and a cathedral’, as she describes it). Or, as Barbara Pym sinisterly hinted in Crampton Hodnet (1985 [1935-1941]):

‘Are there no sick people I ought to visit?’ asked Mr Latimer hopefully.

‘There are no sick people in North Oxford. They are either dead or alive. It’s sometimes difficult to tell the difference, that’s all,’ explained Miss Morrow.

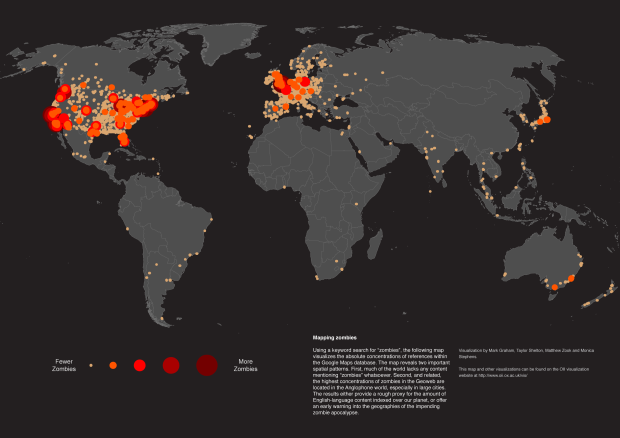

The Oxford Internet Institute has taken this threat seriously: in 2011, it developed a map of the imminent zombie apocalypse. Southeast England is a hub of zombie consciousness, alongside Hollywood and Texas. The city’s timeless apathy is less surprising when you consider the reanimated corpses stumbling along Broad Street.

‘Mapping Zombies’, Oxford Internet Institute, July 2011

So, procrastinators of O-Town, which is it? Misplaced priorities, worldly temptation—or devoured brains?

Like this:

Like Loading...

Nonetheless, we look forward to welcoming the last speaker of the term, the artist and academic Dr Bill Prosser (Oxford) on ‘Drawing—it’s a drag‘. See you, as usual, at 5.30pm in the Old Library, All Souls College for a glass of wine and some stimulating conversation.

Nonetheless, we look forward to welcoming the last speaker of the term, the artist and academic Dr Bill Prosser (Oxford) on ‘Drawing—it’s a drag‘. See you, as usual, at 5.30pm in the Old Library, All Souls College for a glass of wine and some stimulating conversation.

29 October: John McManus,

29 October: John McManus,  Tamara Spitzer-Hobeika,

Tamara Spitzer-Hobeika,

Hurry up please, it’s time.

Hurry up please, it’s time.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.