The ever-interesting author and critic Jane Shilling provided a rather lovely take on our conference on 2 July for today’s Telegraph. See below—or click here for the original.

The Precious Art of Procrastination

Jane Shilling visits the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing to explore procrastination, infamous as being the scourge of creative types

To Oxford, that humming hive of academic endeavour and fantastical far-niente, for a cultural exploration of procrastination convened by the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing.

To Oxford, that humming hive of academic endeavour and fantastical far-niente, for a cultural exploration of procrastination convened by the Oxford Centre for Life-Writing.

Procrastination is notoriously the scourge of creative types, schoolchildren and journalists. Its patron saints are Dr Johnson, frantically scribbling as the printer’s boy waited to snatch the sheets with the ink still wet upon them; Cyril Connolly, morosely cataloguing the sombre impediments to good art (the pram in the hall, the blue bugloss of journalism, the charlock of sex, the slimy mallows of success, etc) while scoffing gulls’ eggs and failing to write a good novel; and Douglas Adams, the modern virtuoso of procrastination, who cheerily admitted that “I love deadlines, I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.”

The sacraments of procrastination are coffee, Red Bull, Pro-Plus and a lurid spectrum of less innocent stimulants. Its ceremonies are the missed deadline, the specious excuse and the exasperated riposte of the schoolmaster and editor. (I find there is something strangely comforting—even addictive—about the increasingly desperate enquiries of my editors as to when I might eventually file my copy. I tend to reply in the immortal words of Captain Jack Aubrey’s rebarbative steward Killick. Questioned as to the whereabouts of the Captain’s eagerly awaited dinner, he remarked dourly, “Which it will be ready when it is ready”.)

If procrastination were merely an example of what the Greeks termed akrasia—the habit of acting against one’s better judgment—it would be of compelling interest to philosophers and psychologists, but its role in artistic endeavour would be essentially that of the bad fairy at the christening. Happily, when it comes to creativity, procrastination has the mysterious homeopathic quality of being both poison and cure, inspiration and inhibitor.

The OCLW’s procrastination blog (at ProcrastinationOxford.org) offers a picaresque tour of the procrastinatory horizon, taking in such monuments of the art of stylish cunctation as the flâneur—the 19th-century embodiment of idleness evoked (and personified) by the poet Baudelaire. In his essay, The Painter of Modern Life, Baudelaire described the flâneur, strolling the city streets in purposeful aimlessness: “The crowd is his element, as the air is that of birds and water of fishes. His passion and his profession are to become one flesh with the crowd.”

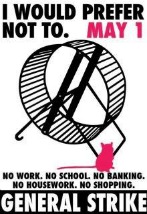

For the Situationist Guy Debord, strolling was a political act. “La dérive”, or drifting, defined as an unplanned journey through an urban landscape, was a medium both of authentic engagement with the “distinct psychic atmospheres” of the city, and a ludic subversion of the grinding monotony of advanced capitalism.

“Ne travaillez jamais”, Debord scrawled on the wall of the rue de Seine in 1953, and it was a maxim to which he adhered throughout his life (a martyr to the effects of lifelong alcoholism, he shot himself in 1994). A visitor to the Debord household observed that Mme Debord seemed to get very little help with the housework. “She does the dishes,” Debord explained. “I do the revolution.”

The fuzzy boundary between work and idleness was a leitmotif of the conference, with papers on “Idle Days in Baghdad: The emergence of bourgeois time and the coffee shop as a site of procrastination”, and the Egyptian novelist, Albert Cossery’s poitics of laziness. Cossery, who remarked that he wrote “only when I have nothing better to do”, produced eight novels in 60 years, written mostly at the Café de Flore, an establishment to which he once turned up in a wheelchair pushed by a beautiful blonde, still wearing the pyjamas of the hospital from which he had just fled.

It was during a paper on Procrastinating Abroad that the God in the machine made an unexpected appearance. We were considering Hieronymus Turler’s 1585 warning to the concerned relations of 16th-century gap-year travellers: (“Three things come out of Italy: a naughty conscience, an empty purse and a weak stomach”) when from somewhere in the roof came the clarion sound of a duo of distinctly unacademic voices engaged in an animated discussion of air vents. Above the sussuration of ruffled scholarly feathers, a quick-witted attendee remarked, “I hate to tell you, but they’re probably working!”

So seductive a subject could scarcely be despatched in a single day. The conversation continues next term at a Procrastination Seminar, to be held on Wednesdays at 5.30pm in the Old Library at All Souls. Further details are said (appropriately enough) to be “coming soon”.

Hurry up please, it’s time.

Hurry up please, it’s time.

One story—our favourite—places the origin of the cult at a convent in Paris. In 1781, a package containing unidentified relics and statutes that had been unearthed at the Denfert-Rochereau catacombs in the city was delivered to the nuns of a nearby convent. Not knowing anything about the martyr to whom the relics belonged, the nuns did what all of us would do: they checked the box for instructions. Lo, the box was marked expedite: the remains must be St. Expeditus! (Forget that expédite is “sender”, please—I’m telling a story.) When their prayers to the new martyr were answered with lightening speed, the cult of Expeditus spread with equal haste across France, and then to all of Christendom. While you wait for the urban legend bells to subside, spare a thought for some nuns duped by express delivery.

One story—our favourite—places the origin of the cult at a convent in Paris. In 1781, a package containing unidentified relics and statutes that had been unearthed at the Denfert-Rochereau catacombs in the city was delivered to the nuns of a nearby convent. Not knowing anything about the martyr to whom the relics belonged, the nuns did what all of us would do: they checked the box for instructions. Lo, the box was marked expedite: the remains must be St. Expeditus! (Forget that expédite is “sender”, please—I’m telling a story.) When their prayers to the new martyr were answered with lightening speed, the cult of Expeditus spread with equal haste across France, and then to all of Christendom. While you wait for the urban legend bells to subside, spare a thought for some nuns duped by express delivery.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.

There is something somnolent in the very air. ‘In Oxford,’ Marías continues, ‘just being requires such concentration and patience, such energy to battle against the natural lethargy of the spirit, that it would be too much to expect its inhabitants actually to stir themselves.’ For centuries the denizens of Oxford have done anything but work. They fornicate and take drugs (Kingsley Amis, Jake’s Thing), ‘snooze…in the arms of Duke Humphrey’ (Dorothy L. Sayers, Gaudy Night), wander the meadows and cart around teddybears. And, worst of all, they write Oxford novels. There were 533 by 1989 alone.